After calling out pirate sites including Vidsrc, HydraHD, and Cineby in a submission to the USTR’s Notorious Markets review, Hollywood’s next targets were put on notice.

After calling out pirate sites including Vidsrc, HydraHD, and Cineby in a submission to the USTR’s Notorious Markets review, Hollywood’s next targets were put on notice.

The MPA’s use of the term ‘hydra’ was a reference to sites that have a tendency to respawn and multiply in response to site blocking measures. In the case of VidSrc, a platform that excels at making piracy simple for many other sites reliant on its services, VidSrc represents the body of a hydra in a piracy-as-a-service wrapper.

Providing a constant flow of content to sites facing potential decapitation is always a threat, but the new action required VidSrc to show some regenerative powers of its own.

Weapons Built in India

With site blocking measures back on the agenda in the United States, seeking an injunction on home soil capable of eliminating or even seriously disrupting a site like VidSrc, would introduce unnecessary risk for very little gain.

A relatively weak injunction would probably have little or no effect, while a big win could call into question the need for new law to support a formal site blocking regime on home soil. When balanced against the benefits of obtaining an injunction in India, of the kind that U.S. courts would be unlikely grant, no better option exists anywhere else.

The injunction obtained at the High Court of New Delhi late September featured members of the MPA and ACE. Beyond Universal City Studios, identifying the rest of the plaintiffs was more difficult than it should’ve been, but we can now confirm them as follows:

• Universal City Studios Productions LLLP (United States)

• Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (United States)

• Netflix US, LLC (United States)

• Disney Enterprises Inc. (United States)

• Apple Video Programming LLC (United States)

• Crunchyroll, LLC (United States)

• SBS Co. Ltd. (Republic of Korea)

• CJ ENM Co. Ltd (Republic of Korea)

• SLL Joongang Co. Ltd. (Republic of Korea)

The scope of the injunction certainly made it stand out. The initial order covered the blocking of 248 domains by local ISPs but also compelled domain registrars worldwide to suspend them within 72 hours.

Framework for Follow-Up Blocking and Suspensions

The real power is the injunction’s ability to tackle any number of replacement domains that subsequently appear to circumvent blocking. The first additional wave of submitted domains is detailed in a follow-up order designed to disrupt VidSrc by blocking and suspending ‘all’ of its domain names at the same time.

In addition to the 248 domains listed in the original injunction (pdf), blocking can also be applied against sites, services, and domains meeting the following criteria:

1. Any site which appears to be associated with any of the previously blocked sites, based on factors including;

• Site name, site branding, site operator’s identity

• Source of the infringing content

• Provision of additional/alternate access to blocked domains

2. Any other site, site owner or anyone else discovered to have been infringing the Plaintiffs’ exclusive rights and/or any other right, including but not limited to hosting, streaming, making available, communicating to the public, or facilitating the same.

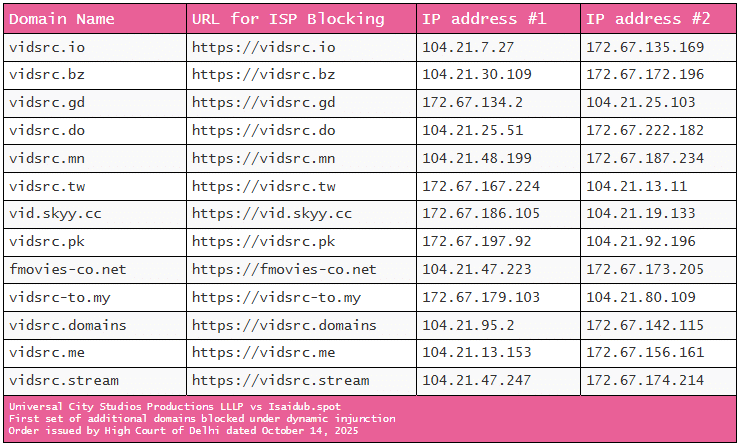

That led to the plaintiffs submitting the following domains; the overwhelming majority are linked to VidSrc and most fulfill all blocking criteria, not just one as required.

The corresponding domain name registrars (DNR) identified by name “and other DNRs, their directors, partners, employees, and all others acting in the capacity of principal or agent acting for and on their behalf,” are directed to;

• Lock and suspend the domains within 72 hours of receiving the order

• Gather personal details relating to the registrant of the domains, including;

• Know-your-customer data, credit card details, mobile number etc.

• Supply that information to the plaintiffs within 72 hours

Precisely when or if these instructions were received by the registrars is unknown.

VidSrc Takes Refuge in Russia

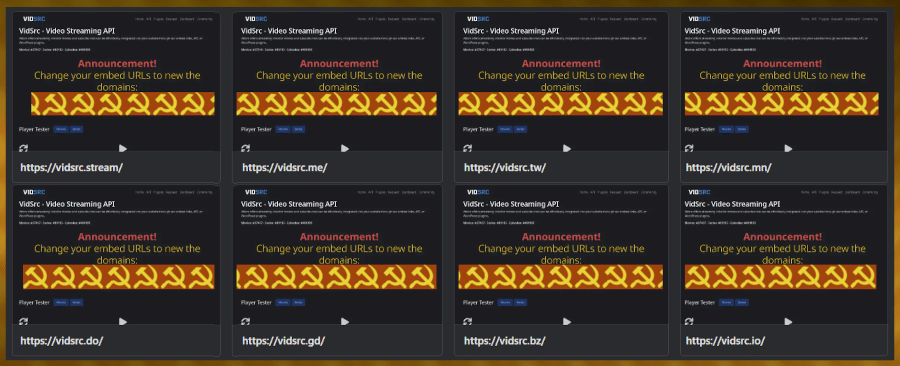

With no obvious signs of enforcement action against its domains and zero element of surprise, VidSrc had plenty of time to take evasive action. In hindsight, it probably responded far more quickly than necessary.

On the front pages of the domains listed for blocking/suspension, notices state that users need to switch to a new set of domains.

While obscured in the image above, the domains are clearly visible when visiting the domains supplied by the rightsholders. All replacement domains are linked to Russia; one carries the .ru ccTLD and the other three use .su, the ccTLD previously allocated to the Soviet Union.

The switch to Russia-linked domains isn’t entirely unexpected. Convincing US-based registrars to suspend domains on behalf of US-based rightsholders, seems more likely to return better results than attempting the same in Russia.

That said, TorrentGalaxy lost control of a .su domain in April 2023. The domain is no longer linked to a torrent site, but it does remain active. If nothing else, it suggests that .su domains aren’t necessarily a stable option. As a long-term option, they’re not suitable at all; the .su ccTLD is expected to be completely phased out by 2030.

Demanding the suspension of the single .ru domain, using the legal avenues available in Russia, to protect U.S. rightsholders brandishing an injunction issued in India, doesn’t sound like an ideal recipe for success. Whether the South Korea-based rightsholders SBS Co. Ltd, CJ ENM Co. Ltd, and SLL Joongang Co. Ltd. continue to do business in Russia is unclear, but beyond local site blocking measures, options for enforcement seem minimal.

Reaction Time Undermined The Order

If the Court’s instructions had been followed to the letter within the 72 hours allocated, the outcome may have been different.

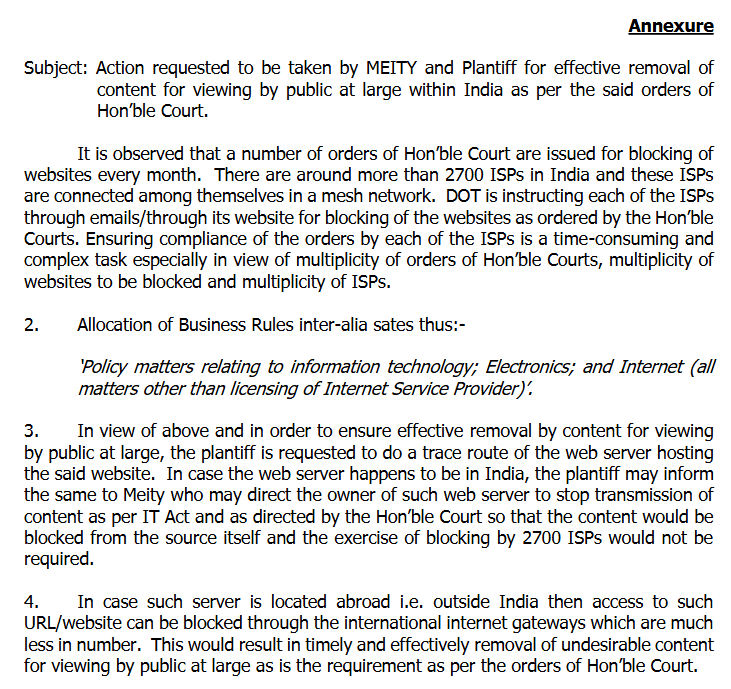

The reasons for the delay at domain registrars is currently unknown. However, it appears the volume of site-blocking instructions handed down by Indian courts, collectively affecting at least tens of thousands, maybe even hundreds of thousands of domains in recent years, is becoming a problem.

The plea is fairly self-explanatory, and while it makes a lot of sense on the ground, it also introduces additional complications.

Under the IT Act, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) could simply order the companies hosting pirate sites to cease doing so. Since that renders the sites immediately inaccessible, blocking at 2,700 ISPs wouldn’t be required, thus easing the administrative load. In the event a site is located outside India, blocking at the gateway level could achieve a similar effect.

The IT Act in India allows the government to block sites under Section 69A on specific grounds, such as national security or public order. The Copyright Act is very clearly not the IT Act, and attempting to find common ground fails at the first hurdle.

The request for the plaintiff to carry out a trace route to each site’s web server, to determine their location, may be well-intentioned. Yet in practical terms, it’s completely baffling. The overwhelming majority of pirate sites use Cloudflare, which ordinarily prevents web servers from being located. In fact, the use of reverse proxies and similar anonymizing technologies were among the main reasons rightsholders turned to blocking injunctions in the first place.

With Indian courts more than happy to grant extraordinarily broad injunctions, at times covering tens of thousands of domains, India has become the website-blocking capital of the world. On paper, at least.

From: TF, for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

Powered by WPeMatico